Last week the Kenyan people went out in droves to vote in a constitutional referendum. The electorate had a simple choice, to either vote “yes” or “no” to the constitutional proposal. The historic referendum was expected by observers to become a first step towards achieving a truly functional government in Kenya, East Africa’s economic power house. Instructively, from dawn, queues of voters had formed in many parts of Kenya. CNN reported “a steady trickle of voters” in Eldoret which thinned down considerably as the day wore out. Eldoret is located in Kenya’s Rift Valley, the scene of some of the worst violence in the aftermath of Kenya’s last election in 2007, which left more than 1, 000 people dead and hundreds homeless.

Many people who joined the queues expressed their determination to become part of history and that sentiment seemed dominant around the 27, 000 polling centers. In all, about 12.5 million voters were registered by the interim independent electoral commission which replaced the discredited body that supervised the 2007 disputed elections. The interim body was also keen to ensure credibility for the referendum result. It said, through a spokesperson, that “many Kenyans were disappointed after the marred 2007 elections. But we have worked hard to restore faith in the country’s electoral body. Systems are in place to ensure that results are thoroughly certified before they are released. The expectations are high and we cannot fail the people”.

One of the most innovative elements of the referendum was the widespread use of the mobile phone as part of an alert system to ensure that illegalities were not perpetrated during the voting. A reporter for The Christian Science Monitor, Mike Pflanz, reported an incident of a local legislator arriving at a polling district and attempting to influence voters to reject the new constitution. And because voting had already commenced, that was illegal; a voter grabbed a mobile phone and sent a text message, which was received in Nairobi, 160 miles from the scene of illegality. Volunteers saw the text and reported to a local electoral official in the district to investigate. That was one of the 1, 230 reports sent by the time the polls closed. It was in fact one of the efforts made in Kenya to “marry traditional election monitoring with social media and internet crowd-sourcing”, according to Pflanz’s report. The transmission of results or the reports of efforts to influence votes was possible because of the popularity of mobile phones in Kenya; there are 12 million mobile phone users in the country, while social networking sites like Facebook and Twitter are soaring in popularity and new blog are regularly launched by Kenyans.

Nevertheless, all kinds of accusations were flying around on the eve of the referendum. Opponents of the draft constitution complained that they were intimidated and there were irregularities. David Koech, an official on the No-Side of the campaign, was quoted as saying that the run up was not free and fair. “There was never a level playing field. The government used state machinery to campaign for the draft. But even so we are confident of victory and in the unlikely event that we lose, we will accept the results if they are not doctored. On the Yes-Side, Kipkorir arap Menjo said the voting had been transparent and that complaints from the opposing side were not valid. “The voting went smoothly, so the claims by the No-Side are just a strategy to reject the result if they are not in their favour”.

Opinion polls in the run up to the vote had consistently indicated that the majority of the voters were likely to approve the draft constitution, because a majority of Kenyans believed that it could usher in some fundamental changes in the way the country is governed. The proponents of the new constitution say that it will check the current excess powers of the Kenyan president; it will devolve power to the regions as well as strengthen the bill of rights. At the forefront of the campaign to get a majority of Kenyans voting for acceptance of the new constitution are President Mwai Kibaki and prime Minister Raila Odinga, who run a coalition government and had jointly pledged these constitutional reforms, after the disputed elections of 2007; as well as Vice president Kalonzo Musyoka and both deputy Prime Ministers, Musalia Mudavadi and Uhuru Kenyatta.

On the No-Side of the debate were members of Christian churches whose objection was based on land rights, a loophole that would potentially allow abortion and the “possible elevation” of one religion over others, with the introduction of Islamic courts. While the draft constitution defines life as beginning at conception, and it also outlaws abortion, it nevertheless includes the exceptions for “emergency treatment, or the life or health of the mother is in danger, or if permitted by any other written law”. The church was labeled as anti-reform, but it rejected the label. CNN quoted Bishop Mark Kariuki of the Deliverance Church, at a prayer meeting the week before the referendum, as saying “No we are not halting reforms. We are saying let’s get good things that are in the constitution, put them in a fridge, then deal with the bad ones”.

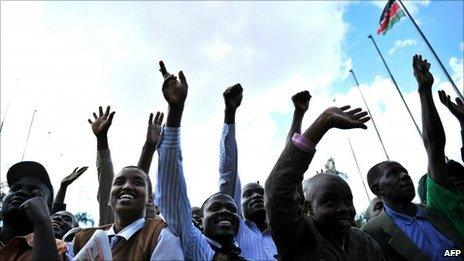

In the end the Yes campaign achieved victory in the referendum, with official results released by the interim electoral body showing 69.9% in favour and 30.7% for the No side; the turnout was 72.2%. The No campaign’s main spokesman, Higher Education Minister, William Ruto, conceded defeat. Interestingly, Ruto had been in the same No group along with the former President, Daniel arap Moi as well as the Minister of Information in the ruling coalition government, Samuel Poghisio. These politicians had argued that the new constitution was not good for Kenya, arguing that the president would still retain excessive powers and that the provisions on land ownership were anti-capitalist. The breakdown of voting showed that most areas of Kenya voted Yes, with the notable exception of the Rift Valley Province, where majority of voters heeded the advice of William Ruto and Daniel arap Moi to vote No. As requested by law, the new Constitution will be signed into law within 14 days of the vote by President Mwai Kibaki.

For those who had campaigned vigorously for a Yes vote, a new day is about to dawn in Kenya. Against the background of the serious crisis which followed in the wake of the 2007 elections, and the mistrust sown within the different peoples of Kenya, it was no surprise that the relative peace within which the referendum was conducted has been welcomed by the international community and the Kenyan people themselves. The run up to the referendum had been largely peaceful, except for isolated incidents of violence, the most serious being the bombing at a Pro-No rally in June, which killed six people in Nairobi. Kenya is one of the economic power houses of Africa; certainly it is the economic hub of East Africa. The new constitution hopes to provide a basis for the deepening of the democratic process in the country and bringing a new lease of life to the Kenyan political process.